| MICROFINANCE |

|

by Valentino Piana (2008) |

| |

| |||||||||

| Contents | ||

| 3. What microcredit is not | ||

| 4. Success factors | ||

| 5. The controversial "zero tolerance" rule | ||

| 6. Integrating health and microfinance | ||

| 7. Micro-insurance | ||

| 9. Micro-savings and other funds for microfinance institutions | ||

| 10. MFIs as healing tools of the societal wounds | ||

| 11. Areas of innovation | ||

|

Take note: More than 128 million of the world's poorest families received a microloan in 2009 | ||

| | ||

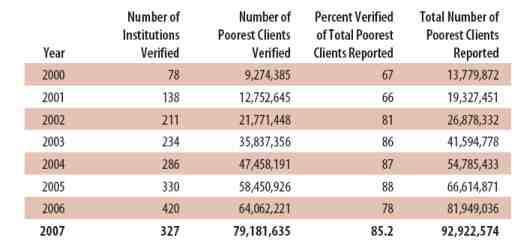

| A platform to deliver financial products and complementary services reaching the poor in order to get them out of poverty. By providing capital, trust, social esteem, information, knowledge, competences, empowerment, networking, social capital, technology and market access, microfinance institutions and other sources of microfinance become active subject in the fight against poverty in all its dimensions and levels. The integral development of the human potential of the client and of her/his family, neighbourhood, and social networks is fostered by both well-established and innovative financial products, whose high repayment ratio, remunerative interest rate (or price) and low administrative cost guarantee the economic sustainability of a well-managed institution. The basic product: microcredit The core product of microfinance is microcredit: an extremely small loan to purchase productive assets boosting the poor's revenue allowing repayment over a short period of time in small instalments without the guarantee of collateral. To experiment a formal model of the effect of such policy use this software and the related paper on the rich and th poor. The size of the loan is small in three dimensions: 1. in absolute monetary values, as compared to typical business loan, so as to operate in a segment where there is no banking competition; 2. in relation to the borrower's income, so that payback is easier; 3. in respect to the lender's portfolio, so that the default of any single borrower has no impact on its financial soundness. The size is kept small for two further lender's reasons: a. for any given portfolio, the smaller the single loan, the larger the number of recipients, thus the wider the outreach over the target population; b. the goal of attracting extremely poor people and keeping the instrument not attractive for the more affluent. This is important since, as a general rule, if both poor and non-poor are eligible to a line of credit, the non-poor will typically crowd-out the poor, obtaining a much larger part of the funds, because non-poor are usually more educated, better informed, more capable of responding to requirements, more at ease in the relationship with the lender. It is possible that the evolution of the target population reduces the number of the extreme poor (or that the threshold for defining them gets higher), thus, in addition to the classical micro-loan, other products are offered (e.g. larger loans). In the standard case, the borrower has already an economic activity (e.g. a shop, a street vendor activity, a handicraft lab,..); when purchasing the asset, her/his productivity is immediately boosted. The asset makes the work faster, with less wasted time and raw materials, increasing the revenue per-worked-hour and the number of effectively worked hours. The revenue boost derives from: a. the radical improvement of highly inefficient productive processes, thanks to capital-embodied innovation; b. the larger scale of operations, thank to larger working capital (the loan is used to buy more raw materials/items to be commercialized, thus boosting the sales); even if operative profitability remains the same, total profits rise because of the larger scale; if there are economies of scale, then profitability raises also in percentage; c. the wider product differentiation of sold products and offered services, including versions of higher quality generating higher profits; d. the larger share in value added going to the worker/borrower, since the loan has given her/him the ownership of means of production, eliminating or reducing the need for external capital and its influence on the decisions. The shoeblack that pays half of this daily turnover to the owner of the shoe brush, by purchasing the brush immediately doubles his own income and become free to go working where he wants. The revenue boost and the large impact on the profitability of the currrent economic activities of the borrower allow for a high interest rate on the loan, which is a crucial issue for the economic sustainability of the lender. The poor can afford to pay a high interest on a year base if the loan is immediately boosting his income and the repayment is just in few weeks. Keeping short the period of reimbursement forces the borrower to concentrate on low-risk improvements of his currenty activity and it is coherent with the short time planning horizon typical of the poor. High frequency of repayment reduce reduce the value of each instalment, easing the task to honour it, and offers more opportunities to monitor how the business is going. This is particularly important since microcredit is not backed by collateral, i.e. goods taken by the fund provider in case of partial or no repayment. The poor usually do not have assets to offer as collateral and, when they have, to take them out would worsen their conditions and income capability, thus would largely be contrary to the same goal of microfinance. Microloans represent sound opportunities of stepwise improvement in the life of the poor. Microfinance starts from basic microloans to provide a host of new variants and complementary services, including payment services, flexibly taking into account the national and local specificities. Since always, moneylenders (the Mexican "coyotes", the Italian "usurai") have provided loans to the poor at extremely high rates, exploiting the emergency need for hot money, leaving the poor in worse conditions after paying back than they were in before. The immediate necessity for money (e.g. to repay a previous debt gone overdue, a funeral, a marriage cerimony, a lost gamble, etc.) forces the poor to accept skyhigh interest rates. Failure in payback begins a vicious cycle of steadily growing indebtness and heavy pressure for repayment, up to menaces and violence. The difference with microcredit is the use of the loan, the dynamics of indebtness, an interest rate that is much higher, the way default and delayed payments are coped with, and, most importantly, the impact on the borrower. Microcredit helps the poor, moneylenders destroy him. In the opposite direction, microcredit is not a subsidised low-interest loan granted for long period of time to a selected few. It is far from nepotistic and clientelistic tools that tend to engender dependency and cynism. The substantial interest forces the poor to reflect on which is the best profitable use of the loan, reducing the need for the lender to orient the investment and to monitor that the loan stick to its stated purpose. As a rule of thumb for the adequate remuneration of the loan, Muhammad Yunus (2007, p. 68) has proposed a Green Zone of interest at the market rate plus up 10 percent, a Yellow Zone which equals the cost of funds at the market rate plus 10 to 15 percent, and a Red Zone, where the rate is higher than in the Yellow one and which is the moneylenders' territory. The lending institution cannot afford a huge number of small loan procedures if the administrative cost of each procedure is high: it has to be be much smaller than in a bank, shifting the burden of proof from the operation to the personality of the client. A deep understanding of her/his history, way of thinking, motivation, trustworthiness, bonds to the family and the neighbourhood, reasons for being poor allows a successful long-term relationship made up of recurrent loans each fostering an advancement in her/his life. The theory of games has widely shown that repetitive "games" (loans) generate a setting where it is better for the borrower to pay back (so to have the perspective of obtaining trust again) than to cheat. Successful as they are, "tit-for-tat" strategies rely on the first positive move of the lender, who trust first, engendering an economic effect reinforcing the psychological effect of "demonstrating that trust was deserved". Microfinance offices are located near the clients, lenders and officers meet often and there is a social control due to face-to-face interaction in a neighbourhood. In some instances, microfinance officers may even renounce to stable physical offices to travel and stay by their potential clients, guested in their houses. High repayment ratio, with 98% up to 100% loans paid back on time due, is the single strongest reason exhibited by most microfinance institution to the skeptical financial and political community. Yes, the neglected poor, illiterate and lacking formal training, living in doubtful hygienic conditions, after a life of oppression and emargination can be good and remunerative client of financial products, keeping their promises and activating all their entrepreneurial and personal energies. Conversely, to keep the monitoring costs low, many microfinance institutions (MFIs) require the borrower to set up a group of peers involved in a cycle of conditional loans. For one member to obtain the loan, the previous receiver has to pay regularly back. The group exerts surveillance on each member, helps in coping with difficulties and reduces to zero the "idle" time, when the money paid back remains in the institution before being given to a new borrower. To compete with them, other institutions are offering individual loans, but they should have mechanism to cope with the higher monitoring costs and the (potentially) worse portfolio at risk. A further key success factor is the recruitment policy of the micro finance institution, which should select people caring about the broader goal of the organization, willing to constantly upgrade their technical and relational competences, and honest. A special monitoring system should indeed be in place to check for dishonest appropriation, which is relatively easy in the business. Technology should be applied to record transactions, but crucial is the organizational double check of clients and employees. The controversial "zero tolerance" rule Repayment ratio has quickly gained the focal interest of external funders to MFIs and its level below 98% puts the institution under severe scrutiny. Prudential reserves built up to cope with delinquency push the costs up and tend to drive the interest rate higher. If enough MFIs are competing in the same area, this reduces the appeal of the MFI, its turnover, thus the possibility of covering the fixed costs of the personnel and other operative items. To get rid of this thorny nexus of difficulties, some MFIs have established a "zero tolerance" rule to delayed payment. Not even one day, not even one cent. A massive pressure is put on the poor, threatened and pushed to pay. The consequences for the organization are far-reaching. By assuring 100% forced repayment on time, the individual creditworthiness becomes irrelevant, there is less need to scrutiny of her/his personality, everybody asking for a loan is served. This simplifies the administrative procedure cost; the lender's staff can have a low education, the costs for salary, recruitment and training kept to a minimum. Large volumes of credit are matched with low operative costs, which means that the interest rete can be kept very competitively low. The fast delivery of cheap money attracts crowds, taking away clients from the other MFIs and the rentability of each branch is quickly established, boosting the number of new branches (territorial outreach). However all this hinges on the extreme pressure put on the poor each time an instalment comes due. The staff is tough and accepts no reason for even minimal delays, the relationship of trust and respect breaks down, and the harsh face of microfinance gets closer and closer to that of the moneylender. Indeed, if the poor has no money to pay back, he will need to obtain it at the moneylenders, paying back by opening new loans at exorbitant rates, what can easily make his debt soaring. After having timely paid back the micro-loan, she/he is left with a mountain of debt somewhere else. The poor gets poorer, oppressed, exploited, hopeless. To understand the reasons behind default and how to cope with them (ex-ante and ex-post) becomes crucial. If the loan was too high with respect to borrower's current income, than default is particularly easy. Setting low ceilings to loan size proportional to borrowers ability to show regular income would reduce the probability and severity of default, albeit shortening the leap forward in the borrower's life and narrowing the outreach. By coupling the loan with a micro-insurance that operates in case of default, the risk would be eliminated for the lender, while the borrower would be covered by it. However, these financial remedies should be associated with a deeper understanding of the reasons behind default. Integrating health and microfinance Some MFIs have discovered that "health crises are the primary reason microfinance clients default on their loans"; if you have to choose whether buy medicine for your child or payback an instalment, a mother will always choose the former. And this is also in the long-term interest of the lender: if the child does not timely receive cares, her/his health will deteriorate, cares will be even more expensive, time spent for her/him will be detrimental to the income-generating activities of the mother and a host of other negative effects will follow. By reminding the high frequency of instalments, the normally large number of people in the family and the living conditions of the poor exposed to endemic diseases, it's easy to see the high probability of such cases. By providing health care to their clients and their families (directly or - mostly - indirectly), MFIs reduces this risk and its impact, gaining centrality in the life of the borrower, thus positioning themselves better in comparision with competitors [1]. A report on integrating microfinance and healthcare is here. Providing the poor with insurance against risks of any kind is the mission of micro-insurance. A small and repetitive payment covers - in a pool of people - the probability of a negative event deeply effecting one of them. By sharing the risk, the price can be kept low and the disruption to the partners of the affected person can be avoided. For instance, the death of a micro-credit borrower, potentially leading to a negative legacy to the already badly hit family, can be insured so that the debt is eliminated (and the family even given the money for the funeral) while the MFI recovers the money from the insurer. By pooling all the MFI clients, the payment required for covering this risk can be kept quite low. Micro-insurance is getting into new areas such as health risks, property damages in productive assets, wheather-indexed crop insurance for farmers, storm housing damage, etc. These extensions rely on the observation that poverty can easily be the result of negative events, that the poor are the most hit by many widespread risks and that their precautionary savings are freezing badly needed resources. At the same time, the huge number of poor and their wide geographical distribution is an attractive feature for the insurer, since the larger the pool, and the less correlated the events, the lower the payment necessary to cover the negative occurrence, thus its affordability for the poor themselves. These opportunities are at odds with traditional insurance institutions, that are usually excluding the poor from coverage. Micro-franchising for innovative and clean goods A recent development in microfinance is to identify a technological innovation that, embodied in a new durable good or equipment, could improve the life of the poor directly or by the revenues achieved through the commercial sales of the services it provides. For instance, mobile phones have been purchased by poor women in Bangladesh (using a micro-loan) and the services of phone calls sold to the entire village, boosting not only the woman revenues (and her capability of paying back the loan) but also her social centrality ("Before nobody invited me to marriage cerimonies, now I am the first to know and be invited, because they use the phone to invite all the others", as Muhammad Yunus quoted at the Asian-Pacific Microcredit Summit 2008). The key partner is the producer of the innovation or the global service provider (e.g. the mobile phone producer or the phone company) that is crucially interested in selling in rural areas and to the poor. By signing and implementing franchising partnerships with economic giants or new entrants, MFIs become the vehicle of modernization of the areas where they operate, empower the technological level of their clients, and diversify their products. In other cases, the microfinance institution could be selling durable goods directly, operating a commercial margin to contribute to fixed costs. A particularly important categories of durables that should be channelled through this kind of agreements are green clean technologies, e.g. solar-powered lighting systems. In our book on "Innovative Economic Policies for Climate Change Mitigation" we put forth the proposal of leveraging microfinance for the diffusion of clean tech across the poor, so to make coherent and compatible the two goals of poverty eradication and climate change mitigation. Micro-savings and other funds for microfinance institutions Albeit microcredit and other products are fairly rentable, MFIs needs seed money to start and several injections of capital to enlarge their portfolio. Donors are often the source of seed money, but soon MFIs try to obtain loans to overcome minimal thresholds of operation volumes, so to cover fixed expenses. There exist many international specialized funds that provide these loans, whose rating systems can cover both financial soundness and social impact of the MFI. However an even wider creation of specialized funds would give more regional variety and South-South cooperation. Conversely, MFI sometimes find more autonomous sources, like micro-saving accounts offered to poor and non-poor. MFIs as healing tools of the societal wounds By carrying responsibility for the success of their clients and for considering them not only clients but all-rounded persons, MFIs are in a unique position to provide the integrated service needed to "heal" the personal and family difficulties in which the poor would instead replicate themselves. It does not only support the survival strategy of the poor, but provides ground for exiting this condition and fully develop her/his potential. If an MFI chooses to go in this direction, it would throughly listen to the client not only for its immediate purpose but for full personal history and projects, it would help identify standard and non-standard solutions to its wide ranging problems, and provide financial and non-financial services to implement those solutions, directly or by networking with service providers most adequate to the situation (e.g. health care institutions). By replicating this highly personalised service to large groups of poor, MFI are active agents of change in attitudes and behaviour in both a deep and broad sense, favouring political and institutional transformations. The Economics Web Institute is exploring solutions to new and exciting opportunities for MFIs and we would be glad to explain them better to you. As key examples, we enlist here three of them. From remittances to microfinance The Economics Web Institute has developed a consulting package for MFIs wanting to take advantage of the growing trend of migrant remittances as a source of funding. Migrant workers have a crucial monitoring problem about the use of the remittances, too often consumption and not investment, so moral hazard prevents remittances to be as high as potential. By sending money to an MFI which makes a micro-loan to entrepreneurial relatives and friends, the migrant obtain three advantages: 1. the family business develops faster with MFI capital and consulting; 2. a capital is building up in his country; 3. when she/he comes back, the capital will be given back to her/him, who can enter in a managerial position in the family business (e.g. import-export manager), leveraging her/his experience abroad. In turn, this shorten the time horizon of the emigration, strengthening the linkages within the family and with the country of origin, giving rise to a crucial flows of returing migrants to boost endogenous growth of GDP, employment and tax revenue. For further information, you can watch this presentation and ask us for the related topics. Microfinance for entire supply chains MFIs in different locations can turn out to finance broad and overlapping groups of businesses, who could become suppliers and clients to each other. It's frequently the case that, in different times and across different MFIs, their customers comprehend agricultural growers, small processors, craftsmen and manufacturers, street vendors, small shops, and even transport and logistics operators as well as other specialised input and service providers. By acknowledging the potential of commercial cooperation among them to build up coherent and smooth supply chains, networks of MFIs can boost the revenue of their clients, making them more reliable borrowers, as the latter seize the advantage of matching peer counterparts in terms of size, market power, knowledge and attitudes. Conversely, micro-credit for working capital of single firms is somewhat a result of the relatively primitive functioning of the supply chain itself, since in developed conditions, suppliers do not ask cash at delivery but rather emit an invoice, whose payment will be due later on (e.g. 30, 45, 60 or even 120 days after), so to allow the firm to sell and be paid earlier than the supplier. Housing, microfinance and sustainable tourism After overcoming survival goals, the poor is usually interested in improving own housing conditions. However microfinance is not ideal for house extraordinary maintenance, because the house does not produce money itself (it is not a productive asset), thus the loan should be paid out of other sources. The high interest of microcredit becomes easily too high and other financial instruments (e.g. a long-term mortgage housing loan) would be more effective, if only they would not exclude the poor and its extremely small requests. By contrast, if we could make the house a "machine for money", then microfinance institutions (and their priviledged links to the poor) would come back into the formula. This is achieved by transforming the house in a home guesthouse or bed&breakfast (or other regional adaptations), the cornerstone of sustainable tourism where luxurious hotel would mainly enrich foreigner owners by offering out-of-reach services for the local people. For further information, you can watch this presentation and ask us for the related topics. Microfinance enjoys a strong and steady growth worldwide, with the Microcredit Summit Campaign collecting data showing the following results, that confirm that important role of microfinance institutions in poverty reduction:  Number of MFIs by country and number of clients (2006) An Excel calculator of lender and borrower share in the return of a microloan Presentation of a new policy channelling remittances to microfinance Note [1] An extreme example of pro-active MFIs is the "Gender Based Violence Intevention Product", simultaneously addressing social and economic rights at three levels (clients, households and community), to raise awareness and social rejection of gender violence (e.g. husband beating wife, ...), by mixing credit, women empowerment, men training and forums awareness and other instruments; this innovative program is promoted by the Independent Commision for People's Rights and Development - an Indian national level advocacy coalition of over 900 NGOs.

| ||